Into the Heart of the Labyrinth

by Marianne Gambaro

Horse chestnuts, like those collected by my father on the day I was born, stud the pathway to the labyrinth at the yoga center. My mother had been in labor for three days and he, feeling useless and wearied by watching her efforts and by my recalcitrance, had gone for a walk. In the hospital parking lot, he picked up several horse chestnuts that lay scattered on the asphalt in the shadow of their parent tree; that tree had no doubt given birth much more easily than what my mother was enduring.

Each year, my father gave me a handful of horse chestnuts on my birthday until he could no longer find the tree. Or, being a man who held his emotions close, perhaps he decided that I was too old for such sentimentality.

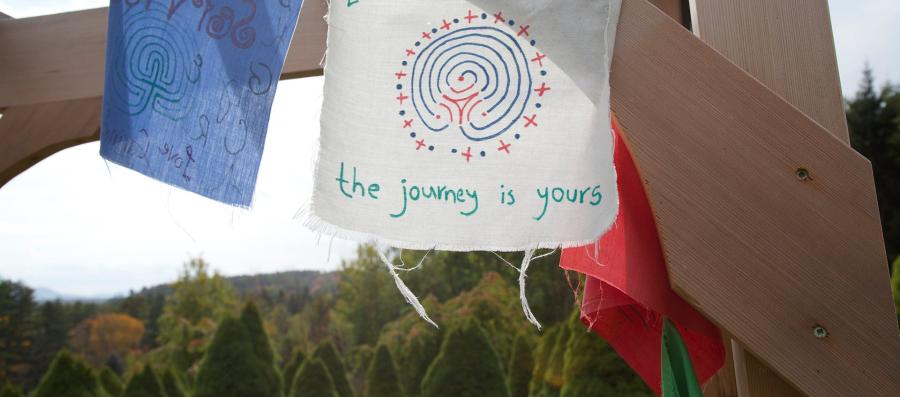

Tibetan prayer flags frame the entry to the Kripalu Labyrinth, fraying their intentions heavenward to the supreme power of choice. Blue tiles and granite cobblestones define the path punctuated by diligently pruned conifers. An errant branch juts out in defiance from an otherwise perfectly manicured hemlock.

One year, away at college on my birthday, I sent my father a cigarillo box filled with horse chestnuts. He never acknowledged my reverse gift. I assumed he thought the postage was a frivolous expense for a student on a budget.

The center of the labyrinth—the goal—is always in sight. It would be so easy to cross the inlaid stones to reach it. So easy to cheat—but why? Isn’t the real goal the journey to find my own center? Like that tired old yoga joke: Yogi to hot dog vendor: “Make me one with everything.” Yogi hands the vendor a twenty-dollar bill and looks at him expectantly, waiting for his change. Vendor to yogi: “Change comes from within.”

Five decades after my birth, it was I who stood at my father’s hospital beds—through bypass surgery, eight years of dialysis, and other ailments that assaulted his once strong body. After he died, as I was emptying out the house where he and my mother had lived for more than half a century, I found that cigarillo box with the horse chestnuts and my note in his nightstand. I threw away the note, but the box still sits on my desk.

To find the center, let go of thoughts and distractions—reflect, meditate, realign, open the mind, tolerate, forgive, accept. To find truth, find meaning; to find meaning, find truth.

Just as the center seems within reach, the path leads teasingly back to the outermost edge. Be open. Be flexible. Embrace change. I find the labyrinth comforting because, unlike life, there is only one path to follow, no choices to be made—one less distraction, one less burden.

Finally, I come to the center. It is cluttered with tributes. A glass bear. A piece of brain coral. Notes scribbled on scraps of paper, even on candy wrappers. And pennies, so many pennies.

I reach into my jacket and pants pockets looking for a tribute and come up empty. Certainly a dirty Kleenex won’t do. I have no part of me to leave here, and wonder why I’ve come after all.

Turning away, I see, half hidden beneath a hemlock, a broken green hull still cradling its charge. My offering. Reverently, I place my tribute in the heart of the labyrinth as I whisper my father’s name and think of the young man who, so many years ago, picked up horse chestnuts in a hospital parking lot while his wife struggled to give me life.

And I begin the journey back out of the labyrinth to find the tree.

Following a career as a journalist and nonprofit public relations professional, Marianne Gambaro writes for the love of words, primarily poetry. More about the author: margampoetry.wordpress.com

This braided essay was originally published in Touch: The Journal of Healing.