The Second Pillar: "Do It Full Out"

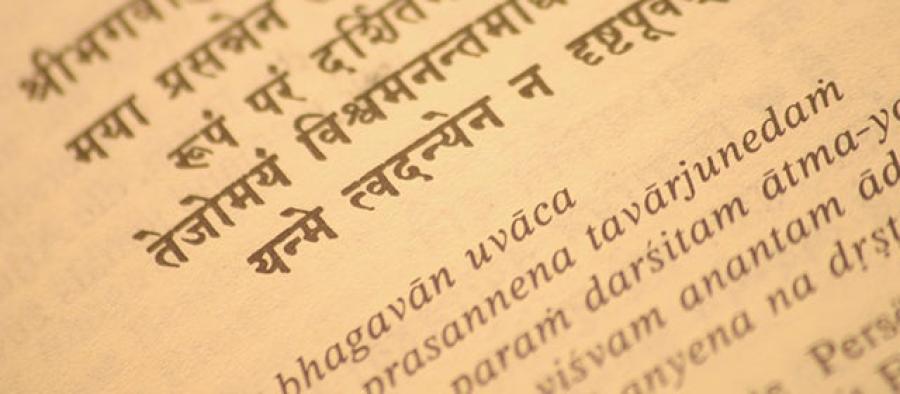

In his book The Great Work of Your Life: A Guide for the Journey to Your True Calling, the founder of the Kripalu Institute for Extraordinary Living uses Krishna and Arjuna’s dialogue in the Bhagavad Gita, as well as the stories of “ordinary” and “extraordinary” lives, as lenses through which to explore the concept of dharma, or sacred duty. In this excerpt, he discusses the second of Krishna’s four pillars of action in the world, known as the Naishkarmya-karman.

I was wandering aimlessly through an art gallery in New York several years ago when I was stopped in my tracks by a stunning Japanese print. It was Katsushika Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa—a stylized print of a mammoth and looming wave framing a distant mountain. I vaguely remembered studying this picture in a college art course. Wasn’t there something about the “innovative artistic tension-arc” created by the moving wave in the foreground and the small-but-unmoving presence of the mountain anchoring the distance? Yes, I could see it now. More than that, I could feel it. In person—at midlife—the print had an energy and power of which I had been oblivious as a college sophomore.

Even more than the print itself, however, I was captivated by the artist’s words about his work—posted on a small ivory card next to the print: “From around the age of six,” the artist began, “I had the habit of sketching from life.” He continues:

“I became an artist, and from fifty on began producing works that won some reputation, but nothing I did before the age of seventy was worthy of attention. At seventy-three, I began to grasp the structures of birds and beasts, insects and fish, and of the way plants grow. If I go on trying, I will surely understand them still better by the time I am eighty-six, so that by ninety I will have penetrated to their essential nature. At one hundred, I may well have a positively divine understanding of them, while at one-hundred and thirty, forty, or more I will have reached the stage where every dot and every stroke I paint will be alive. May Heaven, that grants long life, give me the chance to prove that this is no lie.

Every dot and every stroke I paint will be alive!

Here was a man who was on fire for his work. I wanted to know more: Did he indeed live to be a hundred and forty? What did those later dots and strokes look like?

I sat down on the bench in front of the print and made some notes. “Katsushika Hokusai. 1760–1849. Japanese printmaker. Leading Japanese expert on Chinese painting. Master of the Ukiyo-e form. Nichiren Buddhist.”

Later, at home, I googled Hokusai. He died at eighty-nine, and sure enough, on his deathbed—still looking to penetrate deeper into his art—he had exclaimed, “If only heaven will give me just another ten years … Just another five more years, then I could become a real painter.”

Hokusai was a man who saw his work as a means to “penetrate to the essential nature of things.” And he appears to have succeeded. His work, a hundred and fifty years after his death, could reach right off a gallery wall and grab me in the gut.

More than anything, I was intrigued by the quality of Hokusai’s passion for his work. He helped me to see that a life devoted to dharma can be a deeply ardent life.

***

In the first part of “the wondrous dialogue,” Krishna and Arjuna speak of dharma—its nature, and its role on the path of the fully alive human being. We have spoken so far of what we might call the discernment phase of dharma—the process of sniffing out dharma at every turn. Now comes a new phase: Having found your dharma, embrace it fully and passionately. Bring everything you’ve got to it. Do it full out.

“Considering your dharma, you should not vacillate,” Krishna instructed Arjuna. The vacillating mind is the split mind. The vacillating mind is the doubting mind—the mind at war with itself. “The ignorant, indecisive and lacking in faith, waste their lives,” says Krishna. “They can never be happy in this world or any other.” Ouch.

Well, this Hokusai character was a guy who had not dithered on the path, and had clearly not wasted his life. In fact, he doesn’t seem to have wasted an instant. An interesting aspect of fulfilled lives is that the people who are living them seem to have learned how to gather their energy, how to focus—how to, as we might say these days, “Bring it.” Like Hokusai, their lives begin to look like guided missiles.

How exactly do they accomplish this? How do you get from where most of us live—the run-of-the-mill split mind—to the gathered mind of a Hokusai?

Krishna articulates the principle succinctly: Acting in unity with your purpose itself creates unification. Actions that consciously support dharma have the power to begin to gather our energy. These outward actions, step by step, shape us inwardly. Find your dharma and do it. And in the process of doing it, energy begins to gather itself into a laser beam of effectiveness.

Krishna quickly adds: Do not worry about the outcome. Success or failure are not your concern. It is better to fail at your own dharma than to succeed at the dharma of another. Your task is only to bring as much life force as you can muster to the execution of your dharma. In this spirit, Chinese Master Guan Yin Tzu wrote: “Don’t waste time calculating your chances of success and failure. Just fix your aim and begin.”

From the book THE GREAT WORK OF YOUR LIFE by Stephen Cope. Copyright (c) 2012 by Stephen Cope. Reprinted by arrangement with Bantam Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.