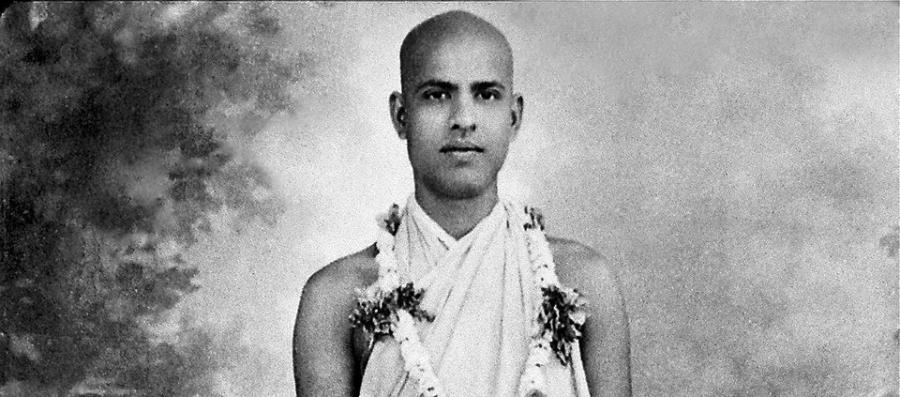

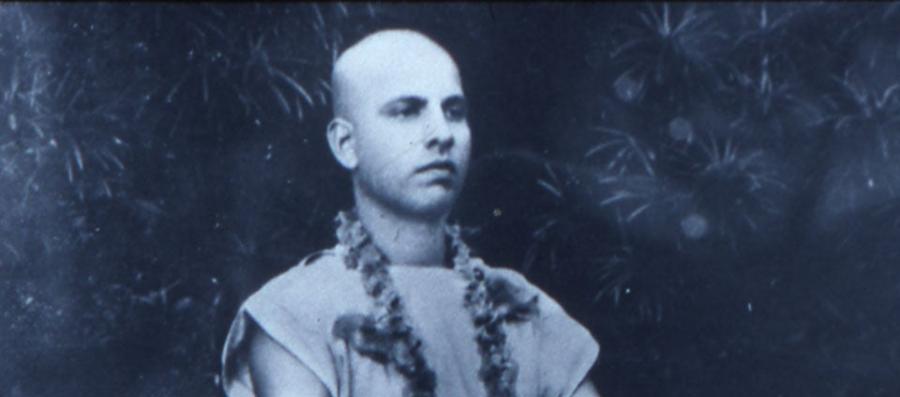

Swami Kripalu’s Early Years

Dharma Then Moksha: The Untold Story of Swami Kripalu, by Richard Faulds (Shobhan), integrates an intensively researched biographical history with Swami Kripalu’s own writings and reflections. In this excerpt, we learn about the young Saraswati Chandra’s family life, education, and early career.

Swami Kripalu was born on January 13, 1913, in an impoverished India just waking up from the spell of shame and subordination cast by 150 years of British rule. His given name was Saraswati Chandra Majmundar, and he grew up in what’s now the state of Gujarat, near the small town of Baroda, in the rustic village of Dabhoi.

Swami Kripalu’s parents were devout members of the Brahmin caste. His father, Jamnadas, started out as a clerk in a lower court of law and advanced to hold the position of Secretary in the Department of Revenue for the Baroda government. He also owned a small plot of agricultural land that he rented out to farmers. While discharging his householder duties, Jamnadas spent most of his spare time in religious worship. Swami Kripalu’s mother, Mangalabahen, ran the household and cared for their two sons and seven daughters. By all accounts, the family was loving and close. Fifth-born and the youngest son, Swami Kripalu was doted on by his mother and older sisters.

In his words …

“A swami cultivates a feeling of love for the entire world by keeping the same affectionate relationship with others that he had with his intimate family members. I have been able to extend the scope of my affection only because of the love I received from my natural family. “

Disaster struck in 1920 when Swami Kripalu’s father died from a sudden illness. The responsibility for the family fell to his mother, who as a high-caste woman was unable to work. Despite the attempt of Swami Kripalu’s affable older brother to step into the role of provider, the family slowly sank into debt. Eventually their home was repossessed, and their belongings put out in the street. Life became a daily struggle to survive and stay together.

Food was scarce, and Swami Kripalu was chided for his growing-boy appetite and inability to refrain from eating on the religious fast days observed by the rest of the family. As his sisters reached maturity, they had difficulty finding suitable husbands as there was no money to pay a dowry. Swami Kripalu was a promising student but had to leave school after sixth grade to work. At 14 years of age, his only option was to conform to social expectations by pursuing a line of work similar to that of his father. His first job was as a tollbooth operator for the township. Eventually his sharp mind and exquisite penmanship enabled him to hold more responsible positions as a municipal tax clerk and later a bookkeeper in a law firm. While industrious and eager to help provide for the family, his inability to pursue an education was a source of great anguish.

In his words …

“When I was very young, my appetite was notorious, and I used to volunteer to distribute the prasad (blessed food) at the temple. Afterwards, when nobody was looking, I used to finish up the leftovers. Truly it was for this special benefit that I took on the service. One might ask if it was by eating all this prasad that I became so religious. If so, there may be very few self-made devotees like me.”

Swami Kripalu did not let his forced departure from school end his education. He was an avid reader and developed a love for all genres of literature. In the evenings he would retire to a quiet spot to study. At 13, he began writing stories, poems, and essays. By 17, several of his pieces had been published in respectable magazines, and he’d written a captivating whodunit detective novel. At only 18 years of age, he’d become a known writer and a thousand copies of his first collection of poems, entitled One Bindu, were printed for sale to an established audience.

Alongside his bookwork, Swami Kripalu had an ear for music and learned to play the harmonium and tamboura from his talented older brother. He also listened to the discourses of the many saints, yogis, and religious leaders who passed through the area.

In his words …

“I have loved literature from my early childhood. There was a rule at the library that you could borrow one book and keep it for 10 days. But every morning I would be waiting at the front of the library before they opened the door to get a new book. Walking down the library steps, I would start reading. There was a marketplace in between our house and the library, and I used to bump into many people on the way home. When I was eating, I would have my book open on the side of the table until my mother would give me a slap on the cheek and make me put it down. At night, I read with a kerosene lamp into the early morning, which caused my sister to get angry and blow out my lamp. This is how I finished a book of a few hundred pages every day. I took out so many books that I helped sweep and clean the library so the librarian wouldn’t feel irritation towards me because I was coming so often. So much love I had for books! It was at that time I learned to study in a methodical manner, holding the mirror of my mind steady so I could observe the subject properly and dwell deeply upon it. All these years later, I still consider myself a student.”

As a youth, Swami Kripalu must have been enthralled by the towering political and religious figure of Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi returned to India in 1915 as a national hero after his successful civil rights campaign in South Africa. The ashram he established in Gujarat on the outskirts of Ahmedabad to serve as his headquarters was only 90 miles from Dabhoi. Swami Kripalu was 17 in 1930, when Gandhi was in the thick of his struggle with the British, writing India’s declaration of independence and marching to the sea to oppose the salt tax.

About this time, Swami Kripalu joined Gandhi’s movement to serve the cause of independence. His nephew Dinesh Majmundar recounts an incident in which Swami Kripalu was dispatched to a nearby village to calm tensions. Unnerved by the religious rancor and vociferous threats of violence, Swami Kripalu was unable to prevent a fracas from arising. When Gandhi arrived to personally quell the disturbance, the youthful Swami Kripalu confessed his failure to the 61-year-old leader and resigned his post. Although his direct participation in the independence movement was short-lived, Swami Kripalu went on to display a Gandhi-like candor and interfaith religious orientation throughout his life.

The young Swami Kripalu's struggles were not yet over. In fact, they would reach a pinnacle with his inability to find full-time work that would force him to the brink of suicide. But the stage was almost set for the young Swami Kripalu to meet his teacher, an encounter that would dramtically shift the trajectory of his future.

Read about a later chapter in Swami Kripalu’s life: