The Blank Page

Michelangelo saw a statue in every block of marble, “shaped and perfect in attitude and action”—an angel waiting to be released. The woodworker George Nakashima believed that when a true craftsman brought out the grain that had been imprisoned in the trunk of a tree, he “found God within.” I’ve long envied those artists who work with materials such as these—clay, marble, granite, wood—because I imagine the feeling is one of collaboration. The material itself contains the shape, the solution. It imposes limits, parameters. If the artist looks and listens carefully, the answer will be revealed: an arm, a thigh, a pattern, an angle, the drape of a robe.

The blank page offers no such gifts. When we greet it, we are quite rightly filled with trepidation. What are you? we wonder. What will you yield to us? The page gazes impassively back. It will give you nothing. It will take everything. It isn’t interested in how we think or what we feel. It doesn’t care if we fill it with words, of if we crumple it up in despair.

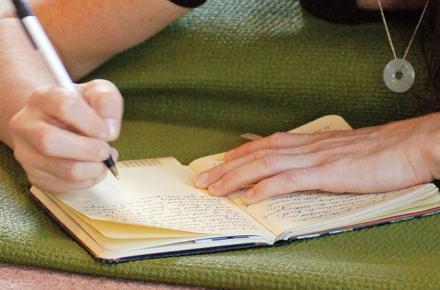

Once, I took an assignment from a newspaper to write something called “Tag Team Fiction.” The idea was to pair two writers to do a story together. One would begin; the other would take up where the story left off; then—tag, you’re it!—back and forth it would go until the story was completed. I was paired with a friend, the writer Meg Wolitzer. I don’t remember which of us began, but I remember the feeling of waking up in the morning and opening my computer to see that my story had magically grown overnight. I had gone to sleep and it had written itself! And it was pretty good, too. Back and forth we went, in a dance, a duet, a writer’s fantasy, which was that the pages seemed to be accumulating on their own, as we slept, or did errands, or went to the gym.

Aside from that one wacky assignment, I’ve never again had the experience of the page giving me anything that I hadn’t put there all by myself. See, the thing is this: you can’t know. You can’t know if it’s going to work. You can’t know if it’s good, or has the potential to be good. You can spend days, weeks, years, working on something that you will end up throwing away, or, in the more gentle way of phrasing it, putting it in a drawer. It’s a lot like the rest of life, in that way. We want to know. Will this relationship work out? Will our children be successful and happy? Will this risk pay off? We fall in love, we have babies, we take risks. The alternative is cowardice. We show up—for life, for writing. We act like brave people, even when we don’t feel like brave people. And so we begin to lay down the words. We fill the page with them. Michelangelo had his marvelous hunks of marble, Nakashima communed with the interiors of trees, and we have this. We are in mid-dive and the words are the water below.

Don’t think too much. There’ll be time to think later. Analysis won’t help. You’re chiseling now. You’re passing your hands over the wood. Now the page is no longer blank. There’s something there. It isn’t your business yet to know whether it’s going to be prize-worthy someday, or whether it will gather dust in a drawer. Now you’re carved the tree. You’ve chiseled the marble. You’ve begun.

This article is excerpted from Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life, by Dani Shapiro.