The Geography of Emotion

A human being is a part of the whole called by us universe, a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feeling as something separated from the rest, a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.

—Albert Einstein

When I’m caught in an emotional storm of sadness, anxiety, excitement, anticipation, grief, or anger, it can be challenging not to identify with the emotion. When I first began meditating, the fluctuating emotions would take over, and I would think of them as “my” emotions. But with the practice of mindfulness, I have the opportunity to be with the emotions rather than become the emotions.

One of my teachers once used a metaphor to describe the human nature of emotion: He described experiencing emotions as visiting a national park—Anxiety National Park, or Sadness National Park, or Hopeful National Park—a place that we all travel to many times throughout life. Each park, or mind state, has its own geography, topography, breadth, and landscape: Sadness National Park has a very different expanse than the National Park of Enthusiasm. In this way, emotion becomes a collective experience, something universal that we all share.

Stepping back from an emotion to observe it more closely can also keep us from getting caught in the storm. Sadness can feel heavy, tight in the chest, cloudy, gray, and static. Anger may feel hot, sharply painful, scratchy, and spreading. Enthusiasm can feel light, airy, and mobile.

When I simply sit with the landscape of a current mind state, I’m not trying to change anything; I’m simply opening to the nature of being human. This compassion for the shared human experience also has an impact on me off the cushion. I feel more connected to my family, friends, coworkers—everyone, really. Pema Chödrön’s book The Places that Scare You: A Guide to Fearlessness in Difficult Times explores this shared human experience; discomfort of any kind becomes the basis for practice. We breathe in, knowing that our pain is shared; there are people all over the earth feeling just as we do right now. This simple gesture is a seed of compassion for self and others. In this way our toothaches, our insomnia, our divorce, and our fears become links with all humanity.

Maria Sirois, PsyD, a Kripalu faculty member, says that positive psychology gives us the permission to be human, and that all feelings are normal and natural. Maria says that we do ourselves great harm when we beat ourselves up about feeling a difficult emotion, like sadness, anxiety, or jealousy. So what’s the antidote? Let the emotions be as they are and give them great compassion, Maria says. When we’re compassionate with ourselves, emotions will flow through with ease. When we negate or deny an emotion, that adds a layer of shame or guilt.

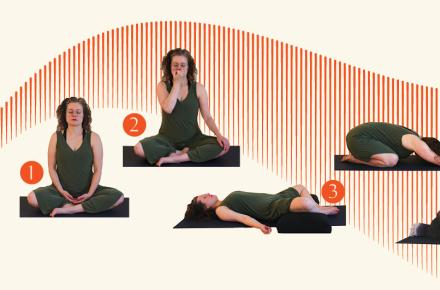

Try this practice: When an emotion arises during meditation practice, name it (sadness, anxiety, enthusiasm, grief, anger, joy). Take a few soft, long, deep breaths. Identify where in the body you feel the emotion most strongly. Keep your attention around that area and softly breathe into the sensation. Next, bring compassion to the sensation; focus on the human nature and shared experience of the emotion. Enter the national park of that emotion, and pause in a moment of recognition that there are millions of people around the world who, at that very moment, are experiencing the same emotion alongside you. Rest in the awareness that millions before and millions after you are having the same human experience. Begin to create some space and separation from the fluctuating mind state, and watch as it arises and falls away with each breath.

Swami Kripalu taught that the highest form of spiritual practice is self-observation without judgment.

The practice of feeling into the connection of shared emotions, done regularly with compassion, can remove the isolation that can come from identifying with feelings such as sadness, anxiety, and grief, and creating a sense of greater connection with the larger web of humankind.

© Kripalu Center for Yoga & Health. All rights reserved. To request permission to reprint, please e-mail editor@kripalu.org.